Cal Dive builds corporate culture with JMJ’s Incident and Injury-Free™ (IIF™) safety approach

Creating a strong safety culture and Incident and Injury-Free workplace delivered measurable improvements.

Creating a strong safety culture and Incident and Injury-Free workplace delivered measurable improvements.

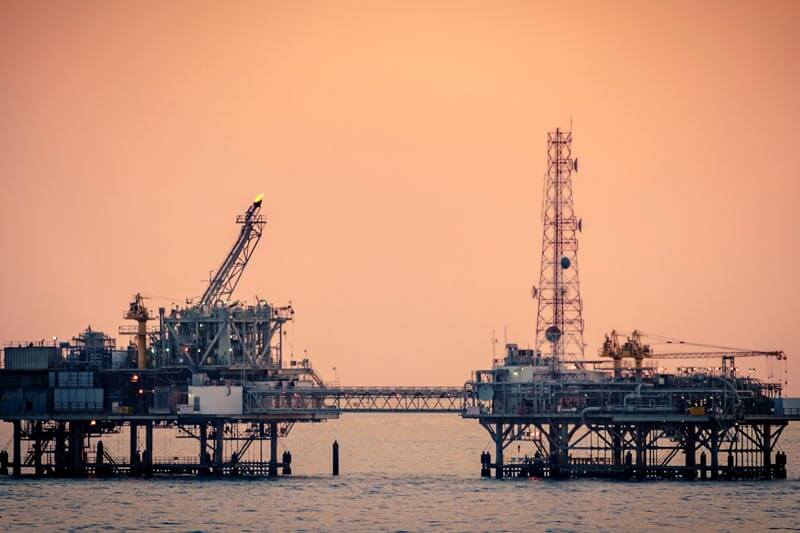

Cal Dive International, Inc., headquartered in Houston, Texas, is the largest commercial diving company in the world. Based on the size of its fleet, Cal Dive is the leader in the diving support business, which provides services including construction, inspection, maintenance, repair and decommissioning of offshore production and pipeline infrastructure on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf and in select international offshore markets, sometimes partnering with other enterprises.

Companies that enjoy market success are not immune to serious problems, especially those engaged in hazardous undertakings. By the end of 2008, Cal Dive had experienced three fatalities in the previous eighteen months, rocking the family-friendly company and its employees to their roots. Cal Dive had never experienced anything like this—it had developed completely unwanted and unwelcome expertise in coping with human tragedy. The company had a robust safety program, but somehow it needed to do more.

The fatalities were also a concern to Cal Dive’s client base, largely comprised of multinational energy corporations. These clients are interested in Cal Dive’s safety performance, its safety programs, and its safety leadership.

“In the early days, Cal Dive management’s interest was oriented toward, ‘We have to do this to prove it to our clients,’ rather than, ‘We have to do this to prove it to ourselves,’” according to Pierce. “Allowing an outsider (JMJ) to come in was a huge deal. Management really thought that the company should be able to figure out how not to hurt people by itself.”

JMJ began its work with Cal Dive by conducting company-wide interviews to reveal the collective culture, strengths, values, blind spots, and other relevant information. What was uncovered was compiled into a provocative Report of Findings that was immediately presented to management. “When they finished reading it, as angry as I could tell they were, it was really stirring them. Quinn (Hébert, the company’s Chairman, CEO and President) held the document up and said, ‘This is worth its weight in gold. These people came in here and found out more about us in two weeks than we could have found out in two years.’”

That was the first sign that there was something for the company to gain from the process. Subsequently, Cal Dive’s commitment to creating an IIF workforce really solidified during its first JMJ-led Commitment Workshop—a process that focuses on getting key influencers in the organization to address two questions: Will you be responsible for your company being incident and injury-free? Are you willing to be held accountable for having said so?

According to Pierce, one group reported out to its peers, “No, it’s just not possible. We’re not going to be incident-and injury-free.” That response ignited a team member from a different group to stand up and passionately share what he had observed in himself—that not only is achieving IIF results possible, but the way that he had been as a leader was inadequate to produce what he saw as the possibility. “This is a hardened 20-year guy in the offshore oil business. He had a moment that impacted the entire workshop and ultimately the entire company,” Pierce said. “It was in that moment, during a break, when Cal Dive leaders came to me and said, ‘We have to do more of this work. We had no idea that this type of transformation was possible inside our people—that they could see something we couldn’t see for ourselves.’”

From that point, Cal Dive’s safety journey started gaining momentum. There was a very different feel in the company.

At about the same time that Cal Dive decided to partner with JMJ, the company also was making an acquisition, one of dozens that it has made since commencing operations in 1975. Cal Dive was purchasing a company called Horizon Offshore Contractors, Inc., and like many mergers and acquisitions, it was no secret that they were struggling a bit with integration.

With the acquisition, Cal Dive had two distinct lines of business, which can be characterized as barges and boats. The barges provide marine construction services to the oil and gas industry. Boats represent Cal Dive’s market leading footprint vis-á-vis its DSV fleet, the world’s largest diving corps and the largest array of diving equipment in the world.

In the absence of a close connection between the two companies and cultures, Pierce said, “One of the greatest benefits of the IIF approach is that it has served as probably the strongest business integration tool that we have at Cal Dive. It is the one thing that we all have in common regardless of the legacy company that we come from. Cal Dive is comprised of numerous acquisitions over the years, so a large portion of its employee base does not actually come from Cal Dive originally. The IIFapproach has been a fabulous integration tool. IIF events that were conducted—whether an IIF Commitment workshop or a Train-the-Trainer session, or an IIF in Actionworkshop—not only were these programs reinforcing IIF skills, they were serving us in integration in a way we couldn’t have imagined.”

“A focus on creating an IIF workforce brought this company together,” Pierce stated. “We still have a ways to go in our integration, but the walls that have been taken down, and the lines that are starting to blur between the different legacies are a direct result of the company taking on the IIF approach. Regardless of where the leaders at Cal Dive come from, everyone sees the IIF approach with the same value and commitment. It is revered at Cal Dive.”

Cal Dive’s work is inherently hazardous and diverse. Pierce noted, “We have people who work in different positions—divers, plus men and women earning their stripes called tenders—who keep the divers safe by sending equipment and communications below. We have the whole gamut of construction workers onshore, such as welders and riggers. We have crane operators; some vessels hold massive cranes, bigger than on dry land. On our boats, the crews are focused in a couple of different areas. One is a professional marine crew, which includes a licensed captain, engineers, etc., that run the boat. Then we have the project personnel who are there to execute the client’s statement of work.”

From the first year of initiating the IIF Safety approach to the second, Cal Dive saw a 25% reduction in Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR). Pierce notes that the most significant metric for Cal Dive, to reinforce leadership’s commitment, is a metric the company refers to as the Cost of Safety. As an offshore company, Cal Dive is required to take care of anyone who becomes injured or ill while offshore. So if a person suffers a broken tooth or any type of personal illness working offshore, the Jones Act requires that the employer cover all expenses—hospital, food, doctor bills, prescriptions, hotels, rehabilitation if required, and so on. Annually for Cal Dive, that number has been quite large, in the eight-figure range for work-related or non-work-related events. In 2009, Cal Dive’s goal was to reduce that amount by 25% while putting people’s health and safety first.

Pierce recounts a quote from Cal Dive’s CEO, Quinn Hébert, speaking to an employee about the importance of safety. “This is about people not getting hurt working for this company. It saddens me that we know how well to respond to a catastrophic event. I never want to have to do that again. When I tell you that I care about you, that is exactly what I mean—we care about your health and your safety. Saving money is a benefit of the program, to be sure. But this is not about saving money; it’s about saving lives.”